Take a look at previous What We’re Reading blogs for more reading inspiration.

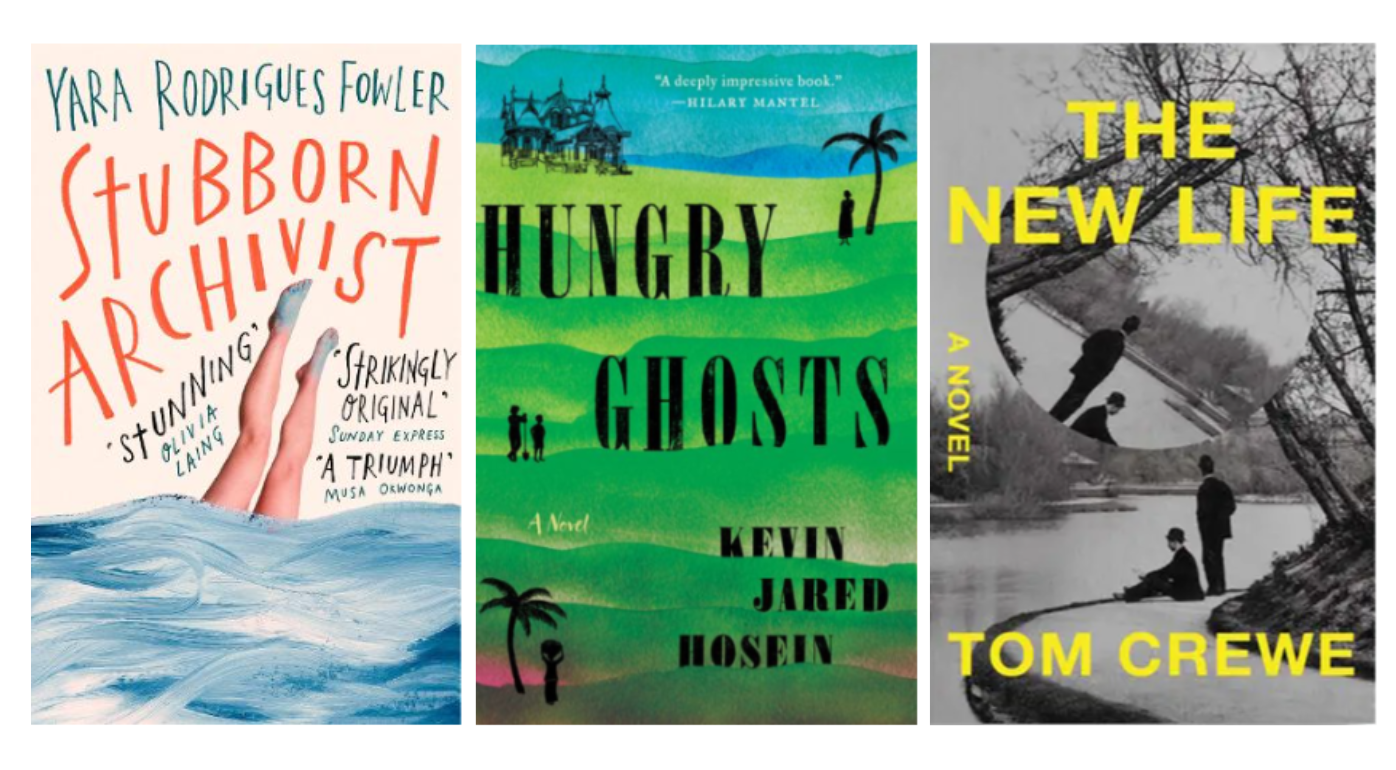

Hungry Ghosts, by Kevin Jared Hosein

I'm thoroughly enjoying Hungry Ghosts, the debut novel by Kevin Jared Hosein, who won the Commonwealth Short Story Prize in 2018, and whom I had the pleasure of hearing read at the Bocas Lit Fest in Trinidad and Tobago.

It's 1940s rural Trinidad, and there's a storm brewing. Quite literally, in the shape of torrential downpours which impact the lives of the ensemble cast of characters: Hansraj and Shweta, who dream of escaping their leaky barrack for a plot in the nearby town; their son Krishna, who gets into trouble again while out searching flooded paddy fields for fish; and the wealthy businessman Dalton Changoor who mysteriously disappears during the storm, leaving his wife Marlee piecing together his disappearance. But bigger change is also in the air, with the arrival of an American military base and the resulting displacement of families and communities.

I’m only a short way in – so no spoilers here – but this novel has already grabbed my attention with its highly sensory depictions of its characters, its energetic interweaving narratives, as well as the comprehensively portrayed historical backdrop of Trinidad on its journey from a colony to an independent republic. I’m looking forward to more of Kevin Jared Hosein’s writing.

Matthew Beavers, Literature Relationship Manager

The New Life, by Tom Crewe

There is a much quoted line in Tom Crewe’s exquisite novel The New Life 'we must live in the future we hope to make' which so accurately describes the lives of the main characters Henry Ellis and John Addington whose relationship develops through a series of correspondence around a book they are writing together about ‘sexual inversion’. Henry and his wife, Edith, have entered into an experimental non-traditional marriage, whereby they live separately and have their own separate romantic lives, in pursuit of ‘the New Life’, a framework for individual freedom within existing societal structures of England in the 1890s. John by contrast is stuck in a cold and loveless marriage, and moves his lover Frank to live in the family home alongside his wife when his youngest child goes to university, leading to the downfall of his personal and professional life. The novel is inspired by real life events around the time of Oscar Wilde’s trial.

It gives a glimpse of life in Victorian London and attitudes towards homosexuality by focusing in on small careful details, domestic, intimate moments of reflection between the characters that explore the constraints placed upon them. It is the ideas around freedom which I found most striking when reading the book for the first time – freedom of sexuality, of class, of gender and the cost at which individual freedoms are borne by others or trespassed upon.

Rachel Stevens, Director of Literature

The Stubborn Archivist, by Yara Rodrigues Fowler

Fowler's debut novel is a thoughtful meditation on cultural and linguistic identity and what it means to live in between, with the story rooted in South London and parts of Brazil, but also the space in between the two. The story flows backwards and forward across time, and across languages, immersing the reader into the childhood and early adulthood of its protagonist, as she starts dating, goes to university, and starts her first job. Family is at the core of the novel, with the protagonist’s Brazilian mum and English dad centre stage, and the extended Brazilian family, particularly the women coming and going in an almost theatrical manner.

The novel explores the question of what it means to be a woman, a girl, a wife, and the narration, at times in the second person, creates an almost stream of consciousness effect. This builds an immediacy but also a distance for the reader, mirroring the narrators’ relationship with the two countries, that she is both intricately a part of, but by merit of her dual identity, sitting apart from. The form is far from conventional, with some pages reading more like poetry than prose, and just a few words on a page, but the story continues to flow well throughout the book. The writing is very funny at times, particularly when showcasing the stereotypical images held in the UK about Brazil and vice versa.

Perhaps this book will play some part in helping to build a wider understanding of the distinctiveness of Brazil amongst UK readers. I was delighted to see Yara Rodrigues Fowler included on the Granta Best of Young British Novelists’ list this year, and I can’t wait to see where her writing takes her next.

Sinéad Russell, Director of Literature