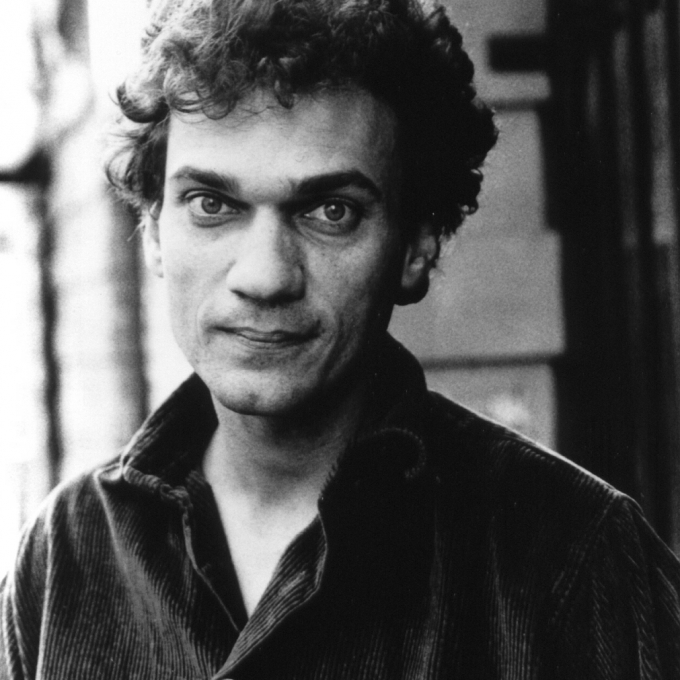

- ©

- Ulla Montan

Biography

Poet and translator Michael Hofmann was born in Freiburg, West Germany in 1957.

The son of the German novelist Gert Hofmann, his translation of his father's novel The Film Explainer won the Independent Foreign Fiction Prize in 1995. He grew up in England and attended schools in Edinburgh and Winchester. He read English Literature and Classics at Magdalene College, Cambridge, and studied as a postgraduate at the University of Regensburg and Trinity College, Cambridge from 1979 to 1983. Since 1983 he has worked as a freelance writer, translator and reviewer. Since 1993, he has held a half-time position at the University of Florida in Gainesville, and in 1994, he was Visiting Associate Professor at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor. He is a member of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences and of the Deutsche Akademie für Sprache und Dichtung.

Michael Hofmann has translated work by Bertolt Brecht, Joseph Roth, Patrick Süskind, Herta Mueller and Franz Kafka. He has twice won the Schlegel-Tieck Prize (Translators' Association), first in 1988 for his adaptation of The Double Bass by Patrick Süskind (1987), and again in 1993 for his translation of Wolfgang Koeppen's Death in Rome (1992). He has twice been the winner of the Oxford-Weidenfeld Translation Prize. His latest translations are Fallada's Alone in Berlin (2009); Angina Days (2010), a translation of selected poems of Gunter Eich; Joseph Roth: A Life in Letterse (2012) and Gottfried Benn's Impromptus: Selected Poems and Some Prose (2013).

His published poetry includes Nights In The Iron Hotel (1983), which won the Cholmondeley Award; Acrimony (1986), which won the Geoffrey Faber Memorial Prize; Corona, Corona (1993) and Approximately Nowhere (1999). His Selected Poems was published in 2008.

In 1994 he co-edited After Ovid: New Metamorphoses with James Lasdun, which included contributions by Ted Hughes and Seamus Heaney. In 2005, he edited the Faber Book of 20th Century German Poems.

Behind the Lines: Pieces on Writing and Pictures, a collection of Michael Hofmann's reviews from the Times Literary Supplement, the London Review of Books, the New York Times and The Times was published in 2001. In 2014 a selection of his essays was published as Where Have You Been?

Michael Hofmann lives in London.

Critical perspective

Two decades since its publication, and most critics are agreed: Michael Hofmann’s Acrimony (1986) looks now like one of the 1980s strongest books of poetry.

Winner of the Geoffrey Faber Memorial Prize, it is a collection that, taken as a whole, demonstrates a poetic of inventive phrase-making, dark humour and acute, detached description at its very best, focusing on two of Hofmann’s recurrent sources of inspiration: the sleazier side of Thatcherite Britain and his complicated relationship with his father, the late novelist Gert Hofmann. In the former, the poems are detailed and evocative studies of environment and atmosphere – ‘Old Labour slogans, Venceremos, dates for demonstrations / like passed deadlines […] / [where] building, repair and demolition / go on simultaneously, indistinguishably’ (‘From Kensal Rise to Heaven’) – while the latter are complex anecdotes of division and terse pathos, peppered with unusual, vivid symbolism fighting to make sense of the difficult bond between father and son: ‘the heraldic plum-tree in your garden / surprising you with its small, rotten fruit’ (‘My Father’s House Has Many Mansions’).

Born in Freiburg, Germany, Hofmann moved to England at the age of four. By the time he was in his early twenties, having graduated from Oxford and studying for a PhD in the poetry of his longstanding poetic mentor, Robert Lowell, his unmistakable poems were appearing in numerous magazines and journals. At the same time as abandoning his studies to move to London, this led to the publication of Hofmann’s first volume, Nights in the Iron Hotel (1983), praised by some for its originality and pithy honesty, criticised by others for its prosiness and frequent aposiopesis: as if, as one reviewer remarked, Hofmann were ‘afraid of something big: perhaps poetry itself’. But Hofmann’s work is somewhat of an acquired taste, and both Nights in the Iron Hotel and Acrimony nonetheless reveal his substantial and varied gifts as a poet, ranging from what Peter Forbes has called the ‘laconic thumbnail formulations’ of unforgettable, rhythmical mantras (‘Acid rain from the Ruhr strips one pine in three …’ from ‘On Fanø’) to what Hofmann himself describes as a penchant for ‘a type of humour where no one quite dares to laugh’ (‘My humour was gravity, so I sat us both in an armchair / and toppled over backwards’ from ‘Ancient Evenings’).

In Hofmann’s third collection, Corona, Corona (1993), a refreshing exploration of new poetic terrain develops, with many of the poems focusing on foreign travel, titles including ‘Sunday in Puebla’, ‘Las Casas’ and ‘Guanajuato Two Times’, among others. This is a topic which Hofmann’s background and peripatetic life – not to mention his characteristically echt poetic style – more than qualify him to write illuminatingly and insightfully on, as in the surreal yet tangible scenes of ‘Postcard from Cuernavaca’:

‘The toilet paper dangles inquiringly from the window cross.

A light bulb’s skull tumbles forlornly into the room.

Outside there is a chained monkey who bites. He lives,

as I do, on Coke and bananas, which he doesn’t trouble to peel.’

While these travel poems may dominate much of the collection’s second half, however, the first section of the book is mainly devoted to character sketches of cultural figures who, both aptly and unsurprisingly, bear the sort of freighted patrimonies that parallel Hofmann’s own. Among them are the Roman general and politician Crassus, ‘whose head was severed a day later than his son’s’, the Victorian ‘fairy-painter, father-slayer, poor, bad, mad’ Richard Dadd, and the famous Motown singer Marvin Gaye, who was killed by his Reverend father, in what Hofmann describes as ‘a dog collar shot a purple dressing-gown, twice.’ As illuminating and well-executed as they may be, however, such pieces do tend towards feeling a little laboured and – even for Hofmann – too thoroughly dejected at times. Fortunately, what Corona, Corona otherwise succeeds in demonstrating is a sharpening of Hofmann’s imaginative stylistic techniques, as in his brilliant use of syllepsis (the drawing together of disparate objects and concepts into the same list) appearing in ‘Freebird’ (‘an electric grille and a siege mentality’) and ‘Guanajuato Two Times’ (‘wearing a pleasant frown and predistressed denims’), as well as his deft handling of extended metaphors, as in that which underpins ‘From A to B and Back Again’ (‘there you were, my brave love, / […] eager to show me / your scars, a couple of tidy crosses / like grappling hooks, one in the metropolis, / the other some distance away, in the unconcerned suburbs’).

In Hofmann’s fourth and most recent collection, Approximately Nowhere (1999), however, the poet’s father once again looms large: the novelist’s death in 1993 coming shortly after the completion of his twelfth book, Lichtenberg and the Little Flower Girl, which, among others, Hofmann has latterly translated. As in Hofmann’s earlier work, he remains a typically adversarial figure throughout the poems (‘the days brutally short; a grumpy early night’) but notably, he is also addressed with a more forgiving – and given his passing – affectingly mournful tone, revealing a calmer and, at times, elegant new dimension to Hofmann’s poetic voice: ‘My father / for once not at his post, not in the penumbra / frowning up from his manuscript at the world’ (‘For Gert Hofmann, died 1 July 1993’). In fact, as Approximately Nowhere’s second half reveals, Hofmann’s increased sympathy for – and greater understanding of – his father has its roots in the poems’ reflections on his own adult life, which in turn mirror childhood memories of his father evident in earlier work. In ‘XXXX’, for example, the poet notes how he is ‘quarrelsome, charming, lustful, inconsolable [and] broken’, before empathetically stating: ‘I have the radio on as much as ever my father did, / carrying it with me from room to room. / I like its level talk.’

While such reconciliatory bridges may seem to offer the reader a strained sort of hope, however, the prevalent attitude of the poems is one distrusting of meliorism: just as history repeats itself, Hofmann suggests, we are doomed as individuals to make much the same mistakes as our forebears; ‘think[ing] continually about money [as] the moths eat [our] clothes’. In a similar vein, the collection also contains some of Hofmann’s most personal poems, documenting the highs and lows of a relationship: ‘the May air full of seeds […] / generative fluff, myself fluffy and generative, / wild-haired and with the taste of L. in my mouth’ (‘Litany’).

In the years since Approximately Nowhere, though, Hofmann’s poetic productivity has dramatically slowed, and the seven pieces at the back of his recent Selected Poems (2008) are representative of nearly a decade’s output. Curiously, this is something which has made – as George Szirtes noted in the Guardian – ‘a Michael Hofmann poem a rare, strange and much valued item’ in recent years, retaining a certain mystery and freshness about his work that some contemporary poets lack. But then as a prolific translator – he has produced more than 40 books, many award-winning, including work by novelists Joseph Roth, Franz Kafka, Fred Wander and, more recently, leading contemporary German poet Durs Grünbein – this seems a natural knock-on effect and occupational hazard of such work; what Hofmann himself describes as a process that ‘takes the words out of you’, as well as distorting ‘your sense of when something is finished’. Whether or not we will see another poetry collection from Hofmann, then, time will tell. But one thing seems certain: his pronounced influence among the current crop of younger British poets is suitable testimony to the value and importance of his poetry to date.

Ben Wilkinson, 2008

Bibliography

Awards

Author statement

'Why I write? With the example of my father before me as I was growing up, it was all I ever wanted, or felt fitted to do. In obedience to a genetic imperative - my father wrote 12 novels in 12 years and dropped dead, my (maternal) grandfather edited the Brockhaus Encyclopaedia. Out of allegiance to certain twentieth-century practitioners, in particular Lowell, Brodsky, Benn and Montale. To bring confusion to my languages, and clarity to myself.'