- ©

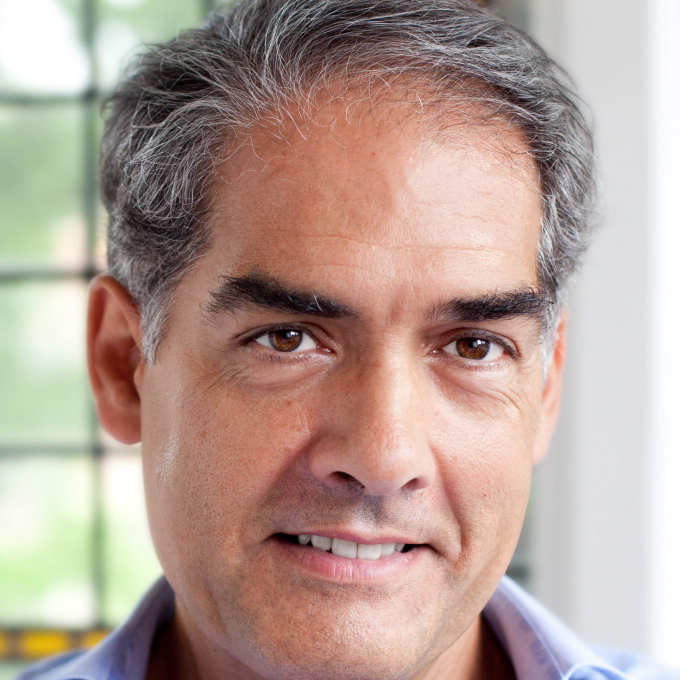

- Joanna Betts

Biography

Philip Kerr was born in Edinburgh and read Law and Philosophy at Birmingham University, subjects which drew him to Germany: “The most interesting legal philosophy is German, so naturally I went to Germany, particularly to Berlin, quite a bit.”

Following university, Kerr worked as a copywriter at a number of advertising agencies, including Saatchi & Saatchi. Here he started working on his first novel about a Berlin-based policeman. His first Bernie Gunther novel, March Violets, was published in 1989.

After leaving advertising, Kerr worked for the London Evening Standard and produced two more novels featuring Bernie Gunther: The Pale Criminal (1990) and A German Requiem (1991). The trilogy was published as an omnibus edition, Berlin Noir, in 1992.

Breaking with Bernie Gunther, Kerr experimented with a range of different forms and stand alone stories over the next two decades, including children’s literature (The Children of the Lamp series), and science fiction (see for example his techno-thriller, A Philosophical Investigation (1993), before returning to his famous Berlin-based detective in The One from the Other (2007) and seven subsequent novels, the latest being The Other Side of Silence (2016). He has also written another series of novels on Scott Manson: January Window (2014); Hand of God (2015); and False Nine (2015)

Philip Kerr passed away in March 2018.

Critical perspective

“I always worry I’ve probably written one too many Bernie Gunther books, and that I should probably give him his gold watch. One or two of the commentators on Amazon seem to think so anyway…”. These are the self-deprecating terms in which Philip Kerr described the cult career of his sardonic ‘wisecracking world-weary’ ex-police officer.

The Berlin-based Bernie Gunther's exploits remain addictive to his readers. The subject of a highly successful series of thrillers spanning twenty-five years, these tightly plotted narratives have taken on a life of their own.

Rather like Conan Doyle’s Sherlock Holmes (whom Doyle killed off in 1893, only to resurrect in 1902), Gunther shows no signs of retiring, let alone stepping into the shadows. Despite taking a sixteen year break from his anti-hero at one point (following the completion of his now classic Berlin Noir trilogy) and the publication of numerous other highly successful stand alone thrillers, historical fictions and children’s books, Kerr’s tenacious crime fighter continues to hog the lime light.

Part of the success of Bernie Gunther can be explained by Kerr’s creative facility with the generic requirements of the form. Plot and pace, dialogue and characterization are particular qualities that have earned Kerr comparison with canonical predecessors from Agatha Christie to Raymond Chandler, from John le Carre to Dashiell Hammett. Meanwhile, the meticulous historical detail of the novels, which take us from Nazi era Germany and the rise of Hitler, to anti-Semitic Argentina, and from the 1930s to the Cold War, have provided vicarious pleasures for a generation of British readers weaned on narratives of World War II and its aftermath.

Many of the formal and historical qualities that would become Kerr’s trademarks are on show in the surgically precise opening of the first Gunther novel, March Violets (1989):

"This morning at the corner of Friedrichstrasse and Jägerstrasse, I saw two men, SA men, unscrewing a red Der Stürmer showcase from the wall of a building. Der Stürmer is the anti-Semitic journal that's run by the Reich's leading Jew-hater, Julius Streicher. The visual impact of these display cases, with their semi-pornographic line-drawings of Aryan maids in the voluptuous embraces of long-nosed monsters tends to attract the weaker-minded reader, providing him with cursory titillation. Respectable people have nothing to do with it."

It is a beginning that displays many of the classic trademarks of crime writing: the firmly urban setting, the rapid establishment of detail and verisimilitude, the fixation on the private eye’s line of sight. Like the best of his type, Gunther’s gaze is morally ambivalent, and unapologetically compromised. Although we do not know it at this point, Gunther gradually emerges as an anti-hero, himself a former SS officer, someone who has obeyed commands of the likes of Himmler and Goering, a womanizer, serious boozer, and serial killer.

In the opening of March Violets, Gunther’s reference to Julius Streicher as a ‘Jew-hater’ appealing to the ‘weaker-minded reader’ implies moral distance, but his presumably parodic reference to Jews as ‘long-nosed monsters’ brings him closer the very ‘cursory titillation’ he otherwise critiques. Gunther goes on to tell us, just a few sentences later, that he wears his hat at the same secretive angle as the Gestapo, ‘with the brim lower in front than at the back’.

Kerr has said that illuminating the contradictions of character through fiction is part of his ethical responsibility as a writer:

"It seems to me that we let humanity off the hook when we describe people, such as the SS, as “monsters” and “bestial”. What they did was only too typical of what human beings do. When you realise that people can do that, rather than monsters and beasts, then everything seems much more horrific."

Field Grey (2010) is perhaps Kerr’s most daring novel in this respect, unraveling Gunther’s collusion with the SS in compelling detail following his arrest by Americans in 1950s Cuba on suspicion of war crimes. In his latest novels in the series, Prague Fatale (2011) and A Man Without Breath (2013) Gunther emerges at his most compromised best. In Prague Fatale, he accepts an invitation to a social gathering with Reinhard Heydrich, the man charged with forging Hitler’s final solution, while in A Man Without Breath Gunther returns to the Eastern front, confronting his own demons while in hot pursuit of others.

Kerr is also author of a string of young adult fantasy novels that together form the Children of the Lamp series (2004-present). Focusing on twins John and Phillipa Gaunt and the discovery that they are in fact genies, the books have become bestsellers. Partly inspired by the Arabian Nights, the series was more immediately motivated by a personal desire to get his sons reading more.

In many ways, the books do the precise opposite of Kerr’s detective novels, abandoning historical fact for magic and make believe; precisely mapped locations for spellbinding adventures. The Akhenaten Adventure (2004) the first novel in the series, opens in Egypt, a world away from the cold, monochrome Berlin of Bernie Gunther:

It was just after noon on a hot summer’s day in Egypt. Hussein Hussaout, his twelve-year-old son, Baksheesh, and their dog, Effendi, were camped in the desert twenty miles south of Cairo … Nothing moved in the desert save a snake, a dung beetle, a small scorpion, and in the distance, a donkey pulling a wooden cart, which was laden with palm leaves, up a dirt track

Kerr himself contextualizes this alternative world well: "Children are missing out on that very important other world, the imaginative world that you can create for yourself". If the pleasures and politics of Kerr’s detective novels reside in their carefully researched realism, in the Children of the Lamp series, it is an embrace of the values of immersive escapism that counts.

However, this rather neat dichotomy does not do justice to Kerr’s broader creative project. Historical fiction is a point of imaginative departure for Kerr, rather than a mirror held up to history. In Hitler’s Peace (2005) the author offers his readers meticulous historical detail in recreating the meeting of Stalin Roosevelt and Churchill in Tehran, in the winter of 1943. It is Kerr’s confident handling of verisimilitude that enables him to render plausible the otherwise unbelievable in that narrative: what if Hitler had negotiated for peace? The same goes for Dark Matter (2002) in which Kerr imaginatively occupies the private life of Sir Isaac Newton in a historical thriller set in 1696. Both books exemplify the wider sense in Kerr’s work, of history as an imaginative resource, rather than a reductive reference point.

As Kerr once suggested in interview, historical detail is less about literalism than impressionism and the imaginative flights and projections it can produce:

"Details are very important. They’re small spots of colour that mean very little close up but when you take several steps back all those little spots of colour start to create a picture. I want to breathe and smell the city myself when I write about it. All of that helps me to make it feel real and to project my own imagination into Bernie’s wide-brimmed hat."

Dr James Procter, 2013