- ©

- Caleb Femi

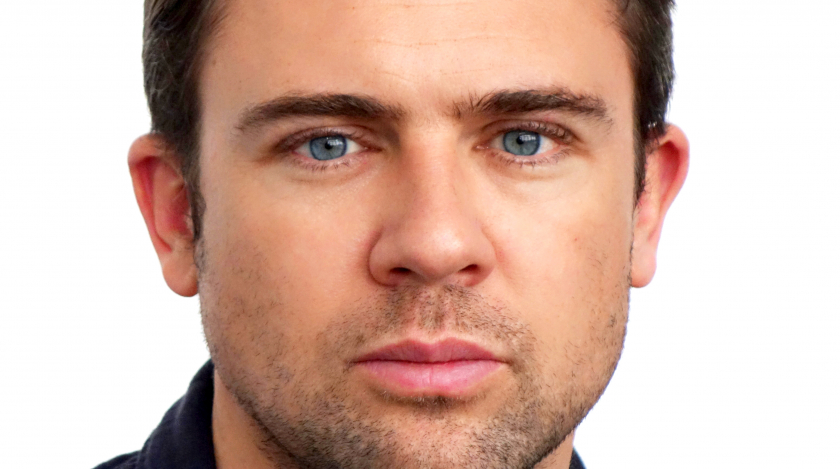

Raymond Antrobus

- Hackney, London

- Penned In The Margins

Biography

Raymond Antrobus is a British-Jamaican poet, editor and educator. He was born in Hackney, London, to a Jamaican father and an English mother. He was one of the first recipients of the MA in Spoken Word Education from Goldsmiths University, and has held fellowships from Cave Canem, Complete Works iii and Jerwood Compton Poetry, as well as residencies in deaf and hearing schools around London. He is a founding member of the spoken-word collective Chill Pill, the Keats House Poets Forum and a board member at The Poetry School.

His poems have appeared in POETRY, Poetry Review, New Statesman and the Deaf Poets Society, as well as in anthologies from Blooadaxe and Nine Arches Press. He has read and performed his work at festivals including Glastonbury and Latitude, at events such as TedXEastEnd, and on BBC 2 and BBC Radio 4. He has also won numerous slams, including the Farrago International Slam 2010 and the Canterbury Slam 2013.

His first pamphlet Shapes & Disfigurements was published by Burning Eye Books in 2012. His second pamphlet, To Sweeten Bitter, was published by Out-Spoken Press in 2017, and his debut collection The Perseverance followed in 2018 from Penned in the Margins. The Perseverance was named a PBS Winter Choice and Poetry Book of the Year 2018 by both The Guardian and The Sunday Times. It also won the Ted Hughes Award, the Sunday Times Young Writer of the Year award, and became the first book of poetry to win the Rathbones Folio prize in 2019. Antrobus was also awarded The Geoffrey Dearmer Prize in 2018 (judged by Ocean Vuong) for his poem ‘Sound Machine’.

His second collection, All The Names Given (Picador / Tin House), was published in 2021 and was shortlisted for the T.S. Eliot Prize. He is also the author of the children's picture book Can Bears Ski? published by Walker Books in 2021 and illustrated by Polly Dunbar.

He currently lives in London, and works nationally and internationally as a poet and teacher.

Critical perspective

The poems of Raymond Antrobus are characterised by misapprehensions, staging everyday encounters with uncanny figures or objects that recur and mislead. In the short unnamed poem that constitutes the epigraph to his 2017 pamphlet To Sweeten Bitter, he writes of one such apparition:

It is not him walking

up the road in that green,

but you follow his oak face

into the garden where his voice

is still slowly growing spaces

too wide without him.

The air is not his blue coat,

His coat is dust and wood smoke.

Hold your tremble,

the man walking the road

is not

your ache.

This scene of misrecognition, at once dream-like and quotidian, provides a fitting introduction to the poems that follow, both in this pamphlet and in the poet’s debut collection The Perseverance (2018). Antrobus’s work is consistently haunted by the death – and turbulent life – of his Jamaican father. Many of his poems give voice to this ‘ache’ of grief in search of an object, and cling to the sensory details of daily life. ‘In the Supermarket’, for example, narrates a shopping trip punctuated by melancholic reminders of the speaker’s father in ‘aisle 5’, and reels off a life’s inventory of ‘West Indian Hot Pepper Sauce’ and ‘Wray and Nephews’ rum. Attention to specificity here amounts to an act of love, as though the poem fulfils Gertrude Stein’s mantra that ‘poetry’ is ‘really loving the name of anything’ (‘Poetry and Grammar’). Like these branded products, which appear to contain the presence of the dead who used them, ‘In the Supermarket’ itself contains a ghost poem comprised of five italicised lines, a formal red herring ruminating on the presence/absence of its lost object, who lies ‘on the shelf or in the ground.’

The title poem of Antrobus’s pamphlet similarly reflects upon language in terms of taste and minutiae. It is framed by the opening image of the ‘three sugars’ his father took ‘in his coffee’. Recalling childhood trips to Jamaica, the poet asks a ‘dictionary/what is difficult about love?/It opened on the word grasp’, a chance signal of his own grasping to ‘accept my father/for who he was/and where he came from’. Sweetening, in Antrobus’s work, is something intimately connected with lineage. Sugar itself is figured as the poet’s lost but recoverable point of origin, as in the poem’s cautionary final lines: ‘how easy it is now to spill/sugar on the table before/it is poured into my cup.’ In ‘Jamaican British’, Antrobus enumerates in anaphoric couplets the vexations of his mixed-race identity, recalling ‘In school I fought a boy in the lunch hall – Jamaican./At home, told Dad, I hate dem, all dem Jamaicans – I’m British.’ His father tells him, ‘you cannot love sugar and hate your sweetness’. This line crystallises the complex nature of hybridity in Antrobus’s work, where it is often described as a tension between the material (‘sugar’) and the conceptual (‘sweetness’). On the blurb to Will Harris’ book Mixed-Race Superman (2018), Antrobus writes that many ‘mixed-race people grow up feeling confused and guilty, because we have to navigate our identities without a language’, but with ‘writers like Will Harris and Zadie Smith a canon of mixed-race literature is emerging that gives us that language.’ Smith’s 2008 essay ‘Speaking in Tongues’ is indeed an illuminating text to read alongside ‘Jamaican British’, as both works problematise the notion of hybridity as a harmonious multiplicity and pay corresponding attention to its fissures.

The hybridity of being mixed-race can be experienced in various and divisive ways, and Antrobus attests to this by interpolating such statements as ‘nothing black about you’ or ‘your skin and hair mean/you’re treated better than us’ in ‘Ode to My Hair’. Central to both To Sweeten Bitter and The Perseverance then, are the numerous kinds of ambivalence that attend Antrobus’s heritage, not only as a condition of mixed-race identity but in relation to the particulars of his father’s life. In as much as these poems constitute a coherent biographical picture, the absent paternal addressee emerges here as a difficult figure with violent and alcoholic tendencies. The title poem of The Perseverance is named after a pub this ‘drinking father’ would always be ‘popping in’ to, and the temporal dimension of this name provides much of the poem’s affective force, with its speaker forever suspended there, waiting ‘outside THE PERSEVERANCE, listening for the laughter.’ Antrobus poses the question of what perseveres – and what is altered or intensified in the process – in numerous representational registers. These range from the ghostly intangibility of memory to the almost vulgar concreteness of the corporeal, as in ‘Thinking of Dad’s Dick’ (inspired by Wayne Holloway-Smith’s poem ‘Dad’s Dick’), which earnestly eulogises the eponymous organ as an heirloom that extends the ‘length of his life to me’.

The Perseverance also addresses other kinds of cultural lineage, and many of the collection’s poems passionately give voice to the inequities and erasures of D/deaf experience. One of the collection’s most arresting moments simply redacts the text of Ted Hughes’ poem ‘Deaf School’. Antrobus describes his ‘intense anger’ upon reading Hughes’ poem, the work of a writer who ‘went into a space, had an interaction he did not understand and felt the need to write this’, a highly insensitive and pseudo-anthropological account of deaf children (which, out of respect to Antrobus’s poem, I do not wish to reproduce here.) As Victoria Adukwei Bulley writes in her review of the collection, this ‘deconstruction of Hughes’s text is not simply an act of writing back but writing over’ (‘To Feel Held’, Poetry London, February 2019), symbolically clearing the space for the poet’s own rewriting. The textual space of The Perseverance is indeed populated with names from D/deaf history, and poems on this subject add another valence to the poet’s recurring interest in questions of following and that which follows. A s he writes to a D/deaf Twitter user in ‘I Move Through London Like a Hotep’, ‘you not being able to follow is not your failure’. All of which is to say that Antrobus’s work is itself at the heart of, though not reducible to, the ‘emerging’ canon he identifies, offering readers a new and vivid ‘language’ of understanding.

Jack Parlett