- ©

- copyright Mark Vessey

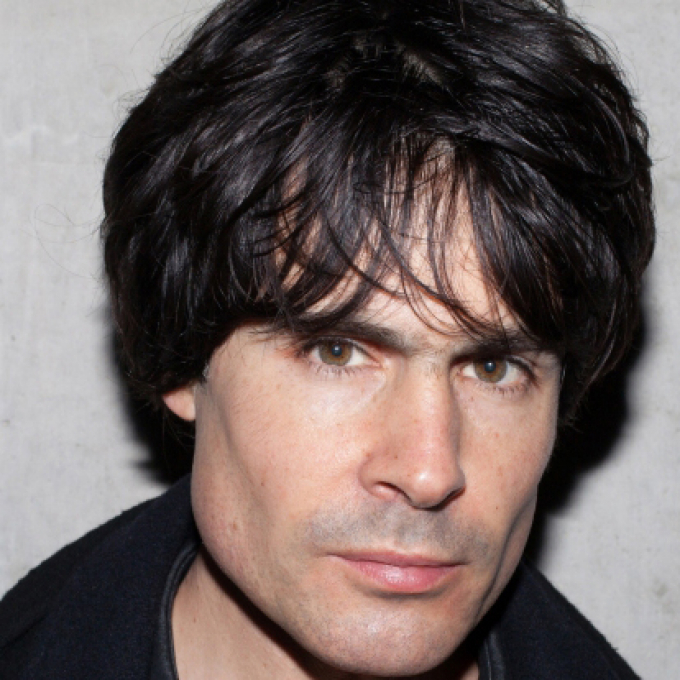

Biography

Sean Borodale was born in London in 1973 and lives in Liverpool and Ireland. He works as a poet and artist, making scriptive and documentary poems written on location. He was Resident Artist & Writer at Bluecoat, Liverpool, 2016-2017 and was Creative Fellow at Trinity College Cambridge from 2013-15.

He was selected as a Granta New Poet in 2012, and his debut collection Bee Journal was shortlisted for the T S Eliot Prize and the Costa Book Award in 2013. Mighty Beast, a documentary poem for Radio 3 won the Radio Academy Gold Award in 2014 for Best Feature or Documentary.

His topographical poem 'Notes for an Atlas' was recommended by Robert Macfarlane in the Guardian Summer Books 2005. It was performed in 2007 at the Southbank Centre’s Royal Festival Hall, directed by Mark Rylance, as part of the first London Festival of Literature.

Borodale’s second collection of poems, Human Work, was published in 2015. Among many projects and residencies to date he was Northern Arts Fellow at the Wordsworth Trust in 1999, and from 2002-7 he was a teaching fellow at the Slade School of Fine Art, UCL.

Critical perspective

As a multidisciplinary artist who has long produced work in the form of exhibition, installation, radio, film and public theatre, Sean Borodale’s reputation as a book-publishing poet is a recently acquired one. His first book-length volume, Notes for an Atlas (2007), offered a sort of topographical poetic impressionism, defying easy categorisation. Nevertheless, its atmospheric and evocative qualities prompted the nature and travel writer Robert Macfarlane to describe it as 'an extraordinary 370-page poem written whilst walking through London, that rings with sadness, haphazardness and utterly modern beauty'. In many ways, it set the style for Borodale’s ongoing, unusual technique of penning poems in the moment, trusting in a hurried process of immediacy and provisionality to capture a kind of poetry in action.

Borodale describes his own writing as 'documentary poems', noting that his 'methodology as a writer often engages with members of the public through interview, and audio/film/written documentation of live events'. It has captivated as many readers as it has occasionally puzzled others, but whatever an audience’s perspective, it is difficult to argue with David Morley’s assessment, writing in Poetry Review, that his 'gritty and wild poems live urgently'.

Described on the book’s cover jacket as a 'startlingly original poetry sequence: a poem-journal of beekeeping that chronicles the life of the hive', Bee Journal (2012) introduced Borodale to a wider readership for the first time. The book offers a documentary-by-poetry written at the hive, wearing veil and gloves, day by month by year. It opens with poems that give an immediate glimpse into the insects’ strange arrival at the family home: 'Bees in the roof, bees on the walls / stitching the house in a net of flightways, / just like surveillance, just like snoopers / in the open air’. Borodale’s writing– wavering, attentive, rhythmically unusual, portentous– succeeds in invoking a felt proximity, the elevated diction and at times almost spiritual intensity owing debts to a lineage of English nature poets, stretching from Alice Oswald back to Ted Hughes and to John Clare. Indeed, Alice Oswald has seen fit to praise Bee Journal, describing the book as 'a kind of uncut-home movie of bees". Noting its "way of catching the world exactly as it happens in the split-second before it sets into poetry'. Oswald classified the writing as 'pre-poems, note-poems dictated by phenomena'.

In its freewheeling approach to craft and revision, the sense that Borodale’s writing exists on the edges of what readers typically expect of poetry is acknowledged by many of the poems themselves. As Bee Journal weaves its chronological narrative– each title is preceded by an accompanying date– the reader uncovers some poems, for example, that are merely a single word (‘1st March’: ‘catkins’; ‘7th March’: ‘snowdrops’) while one in particular is simply titled 'Notes'. 'Listen to the rain, the rain, the rain', it implores, 'like the wings and legs of bees walking across bees, like the lyre of a thought, a whole possible instrument of insects'.

The subject matter may be bees, then, but Borodale’s journal often seems intent, consciously or otherwise, on utilising the hive as an organising metaphor and symbol for a variety of themes. Just as the absent queen is a god-like emblem of hope and uncertainty– 'Today is anxiety. / No presence of the queen, maker of bodies'– the hive becomes thought in action, a kind of manifesto for the poet’s own approach: 'This is a brain itself: congestion of language, / olfactory archive, register / of homeopathic light stored in amphorae'.

Borodale’s follow-up collection, Human Work, appeared in 2015. If the winter honey in Bee Journal is 'dark stuff; mud, tang / of bitter battery-tasting honey', here it becomes a connection between a wild, natural world and our little human universe, accompaniment to toast in our breakfast rituals: 'its calories will burn / (glow-worm light) / in skulls, tonight; // under the hair of children, / in the lamps of brains'.

Human Work is billed as a kind of 'poet’s cookbook', but you would be hard-pressed to rustle up many dishes from its poems. Borodale’s style, as might be expected, is not didactic or even especially structured; rather, the poems are intent on mining the transformative effects of cooking, applying a kind of phenomenological study in exploring how the 'human work' of attending to pot, pan, chopping board, sink and stove reveals something of our nature. Here is a 'Serving of Bream', which once baked sees: 'veins spiderweb the sweet white flakes / of the flesh under the foil; (the face of the moon on the face of the water)'. Elsewhere a heated pan, prepared for venison, 'happens quickly; / the cadence is furious', while the peeling of apples for stewing is a 'flensing; in the factory of the hands // the living opened'. As Borodale himself noted in a piece written for The Poetry Review: 'Stories converge in the mealtime telling, from the growing of food, in its preparation, in the space that is the kitchen. Writing whilst cooking brought a pressure to the act of cooking, frenzy and surprise to the act of writing; a newly defined working grew in the process'.

Despite its dynamic and sensory power, however, Human Work can sometimes seem guilty of overindulgence. Its rich fare may be a source of delight and surprise, but in its ruminative seriousness, the writing may be seen to descend into unintentional bathos. In 'Preparing Potatoes', for example, the 'sombre business' of scrubbing gives way to the grandest of statements: 'They are the gloomy dead, potatoes, / along the walls at Mycenae'. The invocation of mythology and ancient civilisation may extend the poem, but also risks absurdity.

However, Human Work remains an original and surprising volume, testament to Borodale’s unusual compositional approach and fine arts background. As Kate Kellaway noted in The Observer: 'At its best, Borodale’s poetry has the beauty of a still life, but is anything but still'.

Ben Wilkinson, 2017